By Stefany Alvarado, Spring 2021 Intern

In May of 2016, Nabila Rifo’s 28-year-old, bloodied body was found a few blocks from her house in Chile. Rifo’s fractured skull and empty eye sockets were evidence of a brutal assault. In July of 2019, Chile’s neighboring country of Bolivia experienced the attack of Mery Vila, 26. She was beaten with a hammer.

Beyond the Isthmus of Panama and across the Atlantic Ocean, Mexico saw two graphic cases in February of 2020. Ingrid Escamilla, 25, was disemboweled one week before Fátima Cecilia Aldrighett’s 7-year-old body was found in a plastic bag.

These cases have one common factor: women. Each female victim experienced a form of femicide, also referred to as feminicide. The World Health Organization (WHO) and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) define it as “the intentional murder of women because they are women.” More broadly, it is also described as “any killings of women or girls.” The term combines “homicide” and “female” to describe violence against women that results in death.

According to research published by WHO and PAHO in 2012, there are five main types of femicide.

That same year, the United Nations’ Symposium on Femicide expanded on the different forms of femicide to include the following:

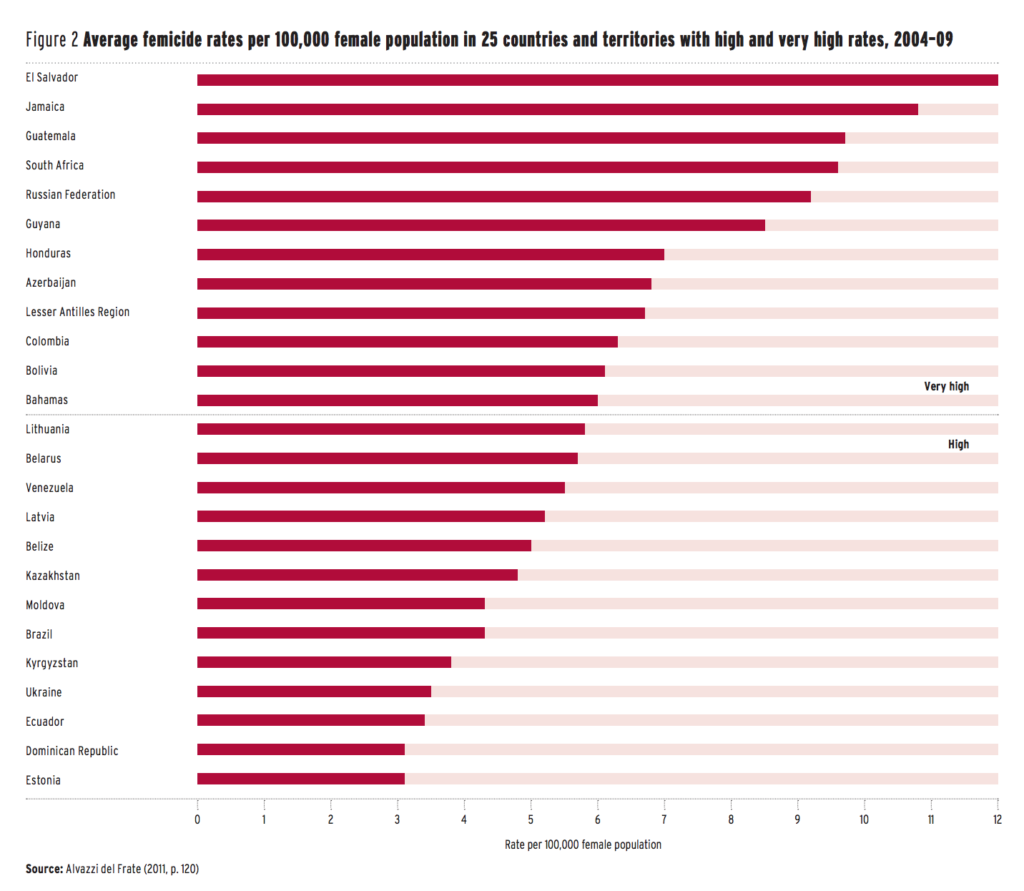

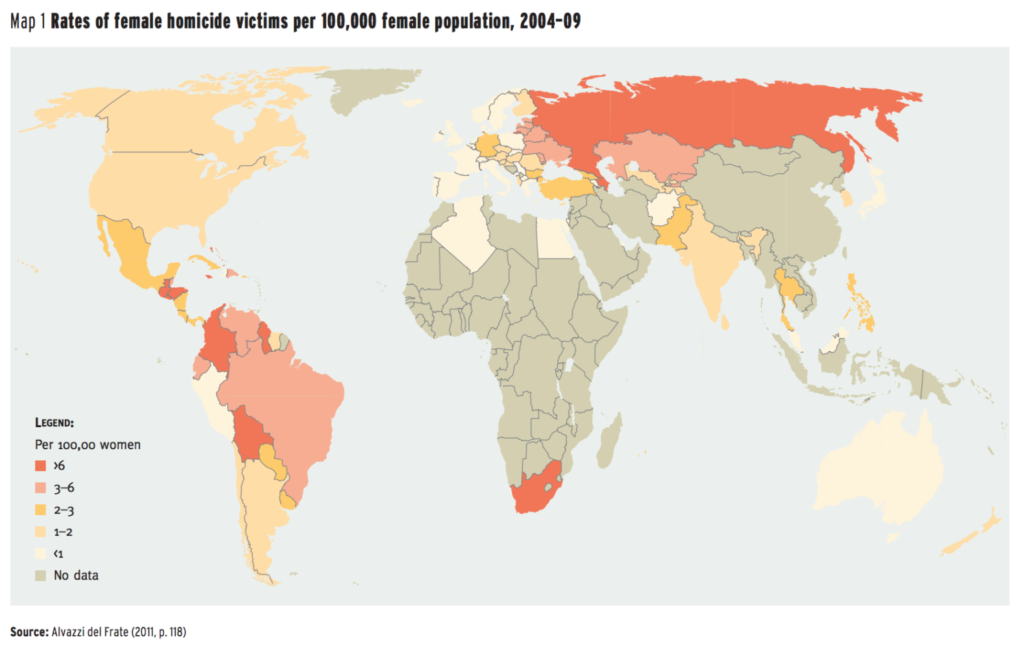

Knowing these listed forms of femicide is essential for understanding the cultural and regional context of each murder. A Small Arms Survey study conducted by the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies in Geneva, Switzerland found that 40% of countries with the highest femicide rates between 2004 and 2009 were Latin American.

In addition, the study showed a concentration of femicides in the Latin Western Hemisphere. Numbers may have differed if adequate data was collected from Africa, Europe and Asia.

There is no denying the international prevalence of femicides, especially in Mexico, Central America and South America. This same phenomenon affecting women in Latin America also exists in the United States.

Though this country has not adopted the term femicide, data exists on fatal outcomes from gender violence against women. In 2007, the U.S. Department of Justice found “intimate partners committed 14% of all homicides in the United States.” Of that intimate partner homicide subgroup, females accounted for 70% of the victims. Later information, compiled from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Multiple Causes of Death, showed that the United States’ female homicide victim rate in 2016 was the highest since 2007.

To contextualize femicide in the United States, Vanessa Guillen’s murder must be reviewed. Guillen was a 20-year-old, Mexican-American soldier stationed in Fort Hood, a U.S. Army post located in Killeen, Texas. She went missing in April of 2020, and her dismembered, burned body was found in June of the same year.

Not every case of female homicide, also known as femicide, will make national headlines like Guillen’s murder. In the state of Georgia, stories of murdered female victims are more readily categorized through statistics. According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), Georgia was the 10th state with the highest number of women murdered by men in 2017. This fact supports the existence of femicide in Georgia, but there is not much precision when identifying the racial and ethnic background of each victim, meaning it is difficult to identify Latinx cases.

No matter the region, whether it’s in Latin America, the United States or Georgia, Latina women are being murdered. There has been an international outcry to end femicide, manifesting itself in protests. For example, women marched in Mexico City on March 8 of last year, also International Women’s Day, calling for the government to take action against gender-based violence. Similar protests occurred a few weeks ago in Venezuela and Mexico.

Though the struggles women endure are overwhelming, steps can be taken to support them and challenge femicide. To start on the individual level, it is essential to listen to, respect and believe women. It is equally important to acknowledge internal biases and actively rewire negative personal perceptions. The same goes for identifying and denouncing sexist vernacular and behavior within social groups.

On a more systemic level, governments must acknowledge and adopt the term femicide into legal jargon. On March 8 of this year, the U.S. House of Representatives introduced a bipartisan bill to renew and improve the Violence Against Women Act, which “creates and supports comprehensive, cost-effective responses to domestic violence, sexual assault, dating violence and stalking,” according to the National Network to End Domestic Violence.

However, femicide is not explicitly identified through United States law as it is in some Latin American countries such as Bolivia, Chile and Peru. Each Latin nation that has codified femicide into law has created criminal procedures specific to the murdering of women. Implementation of these laws has been a challenge, but unlike in the United States, femicide distinct legislature exists.

In addition to legalities, improved data collection and more resources for women would help address femicide. Gathering detailed data is essential because it serves as a guide for institutions looking to create organizations that help women. Caminar Latino is “Georgia’s first and only comprehensive domestic violence intervention program for Latino families.” Data collection would allow for more culture and language specific resources like this to exist. Organizations that support female survivors of violence are integral to combatting femicide because they intervene before physical aggression becomes murder.

Of the four women mentioned at the beginning, only Rifo of Chile survived her attack. Her eyes were gouged out, but she is alive. Rifo is now seeking justice for her attack through Chile’s femicide law.

NOTE: The opinions expressed in this blog are the opinions of the author only. It is not to be assumed that the opinions are those of GALEO or the GALEO Latino Community Development Fund. For the official position on any issue for GALEO, please contact Jerry Gonzalez, CEO of GALEO at jerry@galeo.org.

NOTA: Las opiniones expresadas en este blog son sólo las opiniones del autor. No es de suponer que las opiniones sean de GALEO o el GALEO Latino Community Development Fund. Para la posición oficial sobre cualquier tema de GALEO, por favor contacte a Jerry González, CEO de GALEO en jerry@galeo.org.